Four decades of delay: a 100-year-old accused and an Indian justice system out of time

The Allahabad high court’s decision to acquit a nearly 100-year-old man in a 1982 murder case has thrown a harsh spotlight on India’s judicial delay crisis , where appeals can languish for decades and justice arrives uncomfortably late.

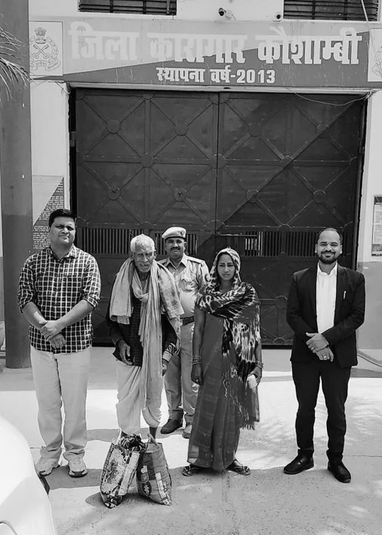

A division bench of justices Chandra Dhari Singh and Sanjiv Kumar acquitted Dhami Ram, noting that over four decades of pendency had passed since he challenged his life sentence. The court said the prolonged uncertainty, anxiety and social consequences suffered by the accused could not be ignored while moulding relief. At the same time, the bench made it clear that the acquittal rested on failure of the prosecution to prove charges beyond reasonable doubt , not merely on humanitarian grounds.

The case dates back to a 1982 land dispute murder , in which three men, Maiku, Satti Din and Dhami Ram, were accused. Maiku absconded, while a sessions court in Hamirpur convicted Satti Din and Dhami Ram in 1984 and sentenced them to life imprisonment. Dhami Ram was released on bail the same year. During the long pendency of the appeal, Satti Din died, leaving Dhami Ram as the sole surviving appellant. He remained on bail for decades until the high court finally disposed of the case and discharged his bail bond.

Beyond the facts of the case, the judgment exposes a deeper systemic failure. India currently has over 4.9 crore pending cases , the bulk of them in district and subordinate courts, which form the base of the judicial pyramid. These delays inevitably spill over into high courts, where lakhs of appeals await final hearing amid serious judge shortages and mounting arrears.

A major but often overlooked reason for such delays is the routine culture of adjournments. The Code of Civil Procedure limits adjournments to three per case , a rule intended to prevent endless postponements and ensure timely progress of hearings. In reality, this provision is rarely enforced. Courts routinely grant adjournments due to overcrowded cause lists, lawyer requests, absence of witnesses or lack of time, turning what should be an exception into standard practice.

The result is a justice system where cases move inch by inch, date after date. Witnesses die, co-accused pass away, memories fade and courts are eventually compelled to weigh age and delay as factors in deciding outcomes. In cases like Dhami Ram’s, an appeal filed in 1984 was resolved only in 2026, illustrating how justice delayed becomes justice distorted .

The judgment therefore raises questions that go far beyond one acquittal. Chronic judge vacancies, insufficient high courts and benches, massive lower court pendency and the non-enforcement of adjournment rules together create a system where delay is structural, not accidental. Unless these root issues are addressed, courts will continue to deliver judgments shaped as much by time lost as by legal merit, eroding confidence in the promise of timely justice.